The announcement this week that Microsoft’s founder, Bill Gates, is to receive an honorary knighthood from Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II seems fitting. For Bill Gates kbe (only British citizens can take the honorific “Sir”) combines knightly philanthropy on an unprecedented scale with a long and impressive combat record. Over the years he has seen off numerous competitors, parrying attacks from all sides and always, somehow, emerging victorious. Microsoft’s most notable success—its establishment, with its Windows software, of a monopoly in desktop operating systems—has led to its fiercest battles of all, as antitrust regulators have accused it of abusing its dominant position.

The story of the company’s epic legal battle with America’s Justice Department and 18 states has passed into legend. In 2000, Microsoft was found guilty of illegally exploiting the dominance of Windows (which is installed on over 95% of pcs worldwide) to gain market share for its web browser over Netscape’s rival product. The company was ordered to be broken up. But the decision was reversed on appeal and a far milder punishment, in the form of restrictions on Microsoft’s behaviour, was applied instead. The case still produces occasional rumbles, like the death-rattle of a mortally wounded dragon, but it no longer poses a threat to the company’s survival.

Now Microsoft is heading for a showdown in Europe where, once again, the company is accused of exploiting its Windows monopoly to take control of adjacent markets, this time in media-player and server software. Intensive negotiations with the European Commission have been under way since the end of last year in an attempt to reach a settlement, though so far without success. A draft ruling against the company, believed to call for the imposition of a $300m-500m fine, along with other remedies, is now said to be circulating within the commission. “The time has come for the commission to reach a conclusion,” says Amelia Torres, a spokeswoman at the competition directorate. “This investigation has been going on for a very long time.”

The European case is particularly important because it concentrates on Microsoft’s behaviour since the imposition of the American settlement, which is widely perceived to have had little effect. At stake, therefore, is the question of whether Microsoft will once again face remedies that treat only narrow instances of past misbehaviour, or if regulators will insist on sanctions that try to eliminate the potential for anti-competitive practices in future.

Both sides are well aware that the outcome could affect the way in which software is developed and sold, as well as the way in which consumers use it. The decision will certainly influence the way in which future antitrust complaints are judged. As it happens, this week Microsoft fired the first arrow in a battle that is widely seen as just such a future antitrust action: its fight with Google over control of the internet-search business.

First, the commission alleged that Microsoft was trying to extend its desktop monopoly into the market for workgroup servers (file, print, mail and web servers) by keeping secret the communications protocols that enable its desktop and server products to talk to each other. “Without such information, alternative server software would be denied a level playing field, as it would be artificially deprived of the opportunity to compete with Microsoft’s products on technical merits alone,” the commission warned in 2001.

Second, Microsoft was accused of trying to extend its monopoly into the media-player market, by incorporating its Windows Media Player (wmp) software into Windows, so ensuring that it would be installed on over 95% of new pcs. Rival products, the commission observed, did not have this advantage; nor could wmp be uninstalled. “The result is a weakening of effective competition in the market … and less innovation,” it concluded.

The latest document bolsters these claims. It uses new evidence from updated market shares to illustrate how Microsoft’s server and media-player have advanced at the expense of rivals. Compared with the drama of the American antitrust action, which included an infamous videotaped deposition from Mr Gates and evidence culled from internal Microsoft e-mails, this is dull stuff. But it does confirm that Microsoft is exploiting its desktop dominance in workgroup server software; and that, by “tying” wmp to Windows, it has overtaken its chief rival in the media-player market, RealNetworks.

Particularly damning are the comments from providers of media content. They say that the cost of supporting different media formats (when providing video clips on a website, for example) leads to a “winner takes all” market which it is difficult for a new media-player, no matter how innovative, to enter. The argument that the efficiencies derived from incorporating wmp into Windows outweigh the anti-competitive effects is dismissed. The commission tellingly observes that the incorporation of wmp in Windows “sends signals which deter innovation” in any technologies which Microsoft could conceivably tie with Windows in the future.

Accordingly, a number of remedies are proposed. The simplest is a fine that reflects the “gravity and duration” of the infringement. European antitrust law allows violators to be fined as much as 10% of their annual worldwide revenues—a fine of more than $3 billion in Microsoft’s case. In addition, Microsoft would be required to license its server-communications protocols to rivals on a “reasonable and non-discriminatory” basis. This is consistent with the settlement that Microsoft reached in America, which also requires it to license some of its protocols.

Following a review of the progress of the American settlement, on January 23rd Microsoft agreed to simplify and extend its licensing programme to encourage wider use. Critics had complained that its previous licensing terms were so complicated that only 11 companies had signed up for them. After the announcement, Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly, who is overseeing the American settlement, declared herself satisfied with the company’s efforts to comply with the settlement.

Far more controversial, however, is the remedy proposed by the commission to address the tying of wmp to Windows. It suggests two alternatives: one forcing Microsoft to “untie” the two products and produce a version of Windows without wmp; the other a “must-carry” approach, which would require Microsoft to include its leading rivals’ media-player software with every copy of Windows.

However, the break-up remedy was overturned on appeal, and the final settlement declared that “the software code that comprises a Windows Operating System product shall be determined by Microsoft in its sole discretion.” Moreover, it did not require Microsoft to remove its web browser from Windows, freeing the company to add other software elements to its operating system.

By adding wmp to Windows, Microsoft is doing exactly that. But is it legal? The company argues that support for the playing of audio and video is part of the core functionality of Windows. Furthermore, it points out that pc-makers are, in the wake of the American settlement, entitled to install media players made by other firms alongside wmp. Hewlett-Packard, for example, recently struck a deal to include Apple’s iTunes music software on its new pcs. But such deals are the exception, not the rule. In December, RealNetworks filed its own $1 billion antitrust suit against Microsoft, complaining that tying wmp to Windows was squeezing it out of the media-player market, just as Netscape was squeezed out of the web-browser market.

Short of a break-up, however, there is no effective antidote to tying. Forcing Microsoft to produce a Europe-specific version of Windows without wmp (or any other specific features) would, in effect, impose an inferior product on European consumers. It is difficult to argue that this would be in their interests. And it would, in any case, probably result in a grey market as the full version of Windows was imported from elsewhere. There are also problems with the must-carry approach: which other media players would be included? Presumably those with the greatest market share. But that would itself be anti-competitive, since it would entrench the positions of the existing players. Furthermore, wmp would still be ubiquitous.

Outwardly, the gulf between Microsoft and the commission in their argument over whether the inclusion of wmp in Windows constitutes illegal tying seems unbridgeable. Last November, three days of closed hearings held in Brussels served only to entrench the two sides’ positions further, according to people familiar with the case.

But both sides would now probably prefer to settle. Microsoft would like to establish a consistent regulatory framework in order to prevent an endless succession of legal battles as it adds more and more new features to Windows. “We want to find a solution that we can apply to future situations, that can be generalised in other situations,” says John Frank, Microsoft’s deputy general counsel.

The commission also seems keen to settle things quickly, having stepped up the legal pace considerably since last August. The number of commissioners will increase from 20 to 30 in May, when ten new member states join the eu; one theory is that the new commissioners will have a more pro-American bent and will be less willing to endorse an anti-Microsoft decision. In any case, the commission has previously expressed a desire to conclude the case before the naming of a new commission president in June.

Reading between the lines, it is just possible to discern the kind of settlement that might now be under discussion: a far wider licensing programme, perhaps one that confers special privileges on companies (such as RealNetworks and Apple) that develop software which competes with parts of Windows. But the devil would be in the details: such a deal might prove to be no more than a grand gesture, allowing the commission to declare victory and then retreat. Microsoft has, after all, shown itself to be a master at running rings around regulators. That said, the commission’s Statement of Objections pre-emptively disallows a number of ways in which Microsoft could evade the proposed tying remedies—which suggests that the commission has learned from past regulatory experiences.

If no agreement is reached, however, and the expected negative ruling is issued, probably in March, Microsoft will appeal. The case will go first to the Court of First Instance in Luxembourg and then (assuming Microsoft loses again) it would move to the European Court of Justice. But all that would take years. Microsoft’s enthusiasm for some kind of early settlement to insulate it from further antitrust action is influenced by the appearance of a third dragon on its horizon. For the firm is currently gearing up for a battle with a new and vigorous competitor: Google.

It is the most visited search site, accounting for 35% of search-engine visits—compared with 28% for Yahoo!, 16% for aol and 15% for Microsoft’s msn, according to comScore Networks, a market-research company. But that masks its true influence. Google’s technology is used to power searches on other sites, such as Yahoo! and aol (though Yahoo! plans to use its own technology soon). Taking this into account makes Google responsible for around 80% of all internet searches. The company is now preparing for a stockmarket flotation in the next few months.

Google’s power makes it just the sort of company that Microsoft typically tries to squash. At the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, Mr Gates admitted that Google’s search technology was “way better” than Microsoft’s, and identified internet search as a key focus for his company. Microsoft already offers searches through msn, its web portal. But until this week it had yet to play its trump card: exploiting its dominance of the web-browser and operating-system markets to extend the reach of its search service. That changed on January 26th when it launched a “toolbar” plug-in for its Internet Explorer browser, enabling instant searches (via msn) from any web page. It is an imitation of Google’s toolbar, which has helped to contribute to the search engine’s success: on a computer screen, as with real estate, location is everything.

Initially, the msn toolbar is a free optional download, as Microsoft’s web browser and media player once were. The next step, inevitably, will be to integrate such search functions into Windows, on the grounds that it constitutes a core technology that should be part of the operating system. In his keynote speech at last November’s Comdex show in Las Vegas, Mr Gates demonstrated a prototype technology called “Stuff I’ve Seen” which does just that. It allows computer users to search for context-specific words in e-mails and in recently visited web pages, as well as in documents on their computers.

In other words, Microsoft is preparing to use its dominance in web-browser and operating-system software to promote itself in yet another separate market—search engines this time—at the expense of competitors. Is that tying? It is entirely possible that, in a few years, the same arguments heard in the American and European cases will again be raging, unresolved. Microsoft will insist that it has done nothing wrong, as competitors cry foul and wizened regulators launch further investigations.

Indeed, the European competition authorities are not the end of the line. Regulators in Brazil and Israel are sharpening their pencils, and Microsoft also faces several outstanding civil lawsuits. The accusation, in each case, is abuse of its Windows monopoly. Will it never end?

There were arduous negotiations. But the remedies, which narrowly addressed the results of the anti-competitive behaviour, ignored treating the underlying cause: the monopoly. Then, as now, regulators stopped short of imposing serious behavioural or structural remedies. So the legal battles have continued ever since.

Ten years on, Microsoft has come to a critical juncture. It can choose to continue its war of attrition with regulators, constantly testing the legal limits and, when it crosses them, treating the consequences as the cost of doing business. Or the company could throw off its monopoly mindset and decide to compete, like most other firms are forced to do, solely on the merits of its products.

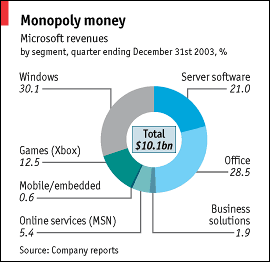

One approach would be to hand some of its Windows protocols over to an independent standards body. This seems unlikely at the moment, particularly given the lucrative nature of the Windows monopoly—Microsoft has just reported record quarterly revenues of over $10 billion (see chart), and much of that is due to Windows. But the company, which already licenses certain protocols to rivals to build inter-operable products, could choose to act as a “common carrier” and license its technology to produce a new revenue stream. Indeed, Microsoft’s actions in complying with the American settlement arguably point in just this direction. A European settlement might push it even further that way.

One approach would be to hand some of its Windows protocols over to an independent standards body. This seems unlikely at the moment, particularly given the lucrative nature of the Windows monopoly—Microsoft has just reported record quarterly revenues of over $10 billion (see chart), and much of that is due to Windows. But the company, which already licenses certain protocols to rivals to build inter-operable products, could choose to act as a “common carrier” and license its technology to produce a new revenue stream. Indeed, Microsoft’s actions in complying with the American settlement arguably point in just this direction. A European settlement might push it even further that way.

Another factor that might tip the balance is the rise of the open-source operating system, Linux. This is not much of a threat to Microsoft’s desktop monopoly, which currently seems secure. Rather, its menace comes from the fact that governments in particular have been early adopters of the open-source system. It is difficult for Microsoft to argue that it is a responsible partner and supplier to governments on the one hand, while doing battle with regulators on the other. So the advance of open-source software in government could have a disproportionate impact.

In other words, Microsoft may some day conclude that the costs of constant regulatory battles—legal costs, fines, bad publicity, and bad relationships with governments—exceed the benefits of its Windows monopoly. This seems unimaginable now. But unless governments find the political will and legal arguments needed to break the firm up, it may be the only way its legal battles will ever end.

Posted by cds at January 31, 2004 03:28 PM